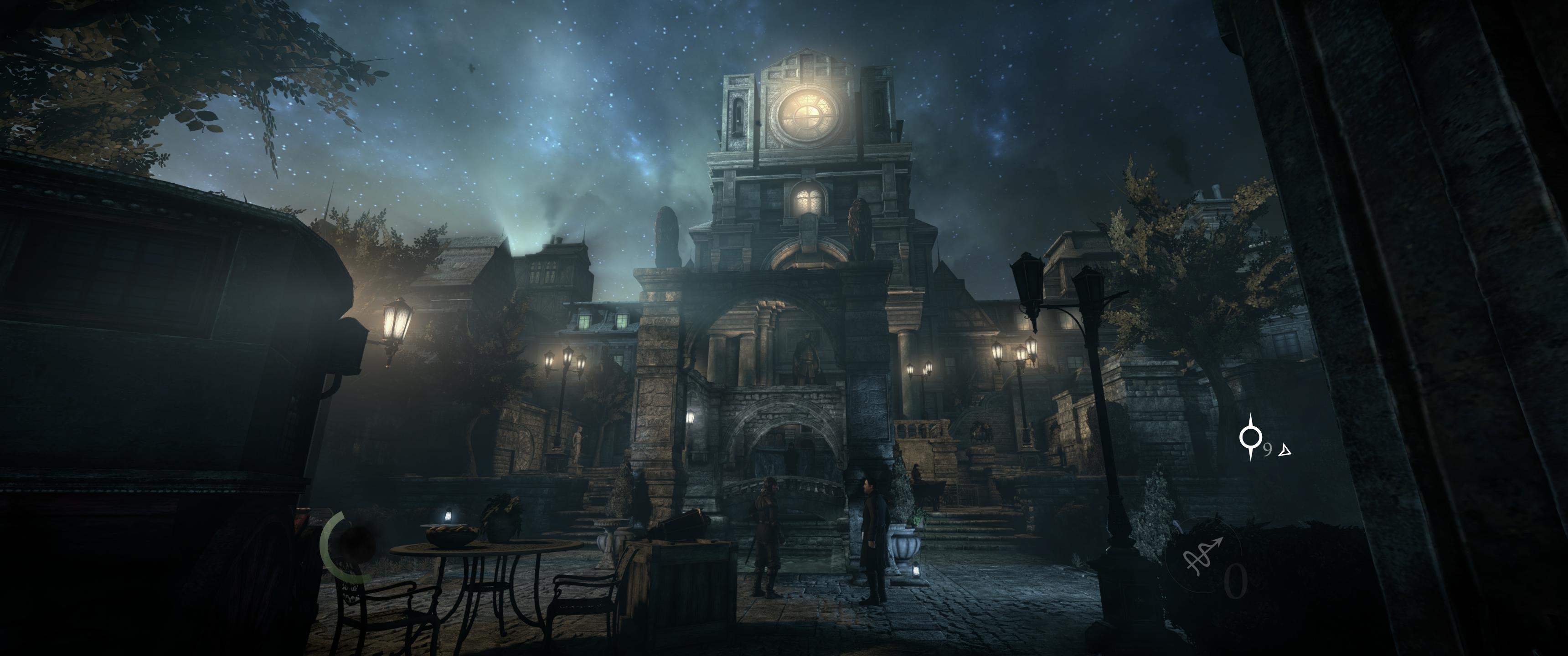

I extinguished some candles and, in the dark, began to crack a safe embedded in the wall. I'd jimmied a rear window and slipped in undetected, swiping cups and inkpots off shelves before sliding into a side room where a guard lay dozing in an armchair. The first wave of relief hit me early, during an opportunistic jewelry shop heist that occurs mid-way through the opening chapter. Thief's settings are a showcase for exemplary art and level design talent, a legacy that begins with Looking Glass Studios and ends with The Dark Mod, with the gaming community.Īfter a linear but necessary tutorial on the rudiments of stealth, climbing, distracting guards and picking locks, Thief opens strong. The latent threat of an Auldale mansion at night, the mysteries of an underground city, the terrors of The Cradle.

For others, it's a game of improvisation, gambits, brawls and hair's breadth escapes.įor many, it's about atmosphere. For some players, Thief is about precision – perfect sequences of evasion and distraction forged with much hammering of the quick load key. It is the actualisation of a very specific fantasy – the outlaw shadow, Robin Hood by way of Batman – and more broadly representative of a particular type of fantasy, a gothic marriage of Hexen's para-medieval grotesquerie and '90s-era steampunk. It stands for the idea that 'first person' doesn't imply 'shooter': the original BioShock might be its great-grandchild, but Amnesia and Gone Home are Thief's descendents too. It is the grandfather of stealth on the PC, part of a design heritage that links Quake to System Shock 2, System Shock 2 to Deus Ex, and so on.

Thief – the series – has been many things.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)